Embodying Jewish Baghdad in Debórah Eliezer’s (dis)Place[d]

Cory Tamler

As you read, hover your mouse over words and phrases underlined in red to reveal excerpts from Debórah Eliezer’s (dis)Place[d] as pop-up text. If on a mobile device, press and hold. Give it a try here.LAND (singing):

Bit-thakkar izzaman elli gubl lughatil ensan

Lamma-ellugha-elwahidi kanat juz'eyyat

Ughniyat alkhabour wal furat...

I remember the time before the language of men. When the only language was elemental: the sound of fish jumping out of the river, the temperature of the wind on skin, the coarseness of the soil under feet. The Land had a personality and I spoke to whomever would listen. And if you were interested in survival, you listened...

Are you listening?

(Land ‘blows’ pieces of map to Daughter. Daughter chokes.)

Debórah Eliezer as the Daughter in (dis)Place[d]. Photo: Wendy Yalom.

Debórah Eliezer’s voice is so material I feel like I could hold it in my hand like a fruit. Her prolific voiceover work is tangible when she speaks. She is quick-talking, hand-talking, and given to casual swearing in a way that puts me at ease. We’re meeting for breakfast the morning after the playwright/performer’s solo show (dis)Place[d] at the 2019 Ko Festival of Performance in Amherst, MA.

(dis)Place[d] is a deeply personal story about Iraqi Jews, whose history in Iraq stretches back thousands of years and who now live almost entirely in diaspora. Told by a daughter of that diaspora, the play stages Baghdad by drawing on fragments of stories and what’s unearthed as her body strains to remember sensations, words, and melodies she didn’t know she knew. It constructs a landscape not from a traditional map but from what’s left after a generation of displacement, assimilation, migration, and participation in settler projects—actions made variously by choice and chance and violence. Together, consciously or not, all surviving Iraqi Jews create this relational landscape that exists only because of the clash of identities produced when a community has to scatter. Maybe this is why Eliezer’s Iraqi cousin (as Eliezer tells me, recounting their recent meeting in her cousin’s home) so eagerly exclaims Talk to me about your show! “She wants it, like she wants to drink it,” Eliezer says. “Because that’s her. But she has not been able to acknowledge that.” Eliezer describes a palpable yearning among Arab Jews today to connect with where their families came from. Stories of Jewish Baghdad are sparse. As in all such cases, the stories that do exist get burdened with the task of representing the entirety of Iraqi Jewish experience. The task’s an impossible one.

From a menu that deploys the word local alongside farm-fresh and organic, like a combined uber-brand, I order an omelet with peaches (a fruit Spanish explorers brought to the Americas in the 1500s) and brie (a soft cheese named after the region of France to which it’s native). One of the key ways Eliezer traces her connection to 1930s Baghdad in the play is through food.EDWARD:

I remember my childhood in Baghdad...every fall my father would get a horse and wagon and the whole family would travel outside the city to pick fruit! In the winter when we went to the hamam, my brothers and I would put beets under the building and eat them after our bath! In the spring and summer we would picnic on the banks of the Tigris and enjoy ourselves, eating a whole fish. Here, in this New England college town, local seems to be shorthand for meal-length absolution from the generic sin of global citizenship and industrial food distribution. It doesn’t have anything to do with where we are.

Eliezer wonders: what would it mean for her cousin, living in a former Palestinian village that’s now peopled by the Iraqi Jewish diaspora, “to sit there and to say, this is our state, and our land, and where we have this country; and then to say, And I came from this other place. And I, too, am an Arab. What will that do to the peace process? To say, I am of you?”

Eating my omelet, I consider the link between fetishizing the local and yearning for connection to place. Both foster the impulse to defend here from not-here. The seeds of violence. Borders. I wonder about whether and how performance can disrupt that link. Performance is uniquely local and uniquely mobile. It’s live, so it’s happening where it’s happening and only there, with those people, in that room. But it can be packed up and taken elsewhere, to happen only in that elsewhere, with those other people, in another room: an entire world is witnessed into life, partially on the stage and partially in each audience member’s mind, but the transferability of that world troubles geographic borders. A place can be a poetic construction, a collaborative waking dream.

But such poetry can in fact translate to new borders. “Even my Arab-Jewish relatives talk about Arabs as ‘the other.’ So what are you even saying with that? What does it mean to be of a place?” Eliezer asked the audience the night before during the post-show discussion. “You’re living in an Arab land!…When you say ‘We’re Jewish,’ what are you saying? We’re not Muslim?” Her questions, though rhetorical, evoke the State of Israel—a state that literalized Jewish longing for a homeland—as one example of the violent exclusion that intertwined claims to identity and claims to land can produce. Will a poetics of landscape 1 always be vulnerable to instrumentalization by those who want to wall off land for their own?

***

Eliezer as Aba. Photo: Wendy Yalom.

Roaming an unfamiliar internal landscape in (dis)Place[d], Eliezer feels, through her body, for answers to the question What does it mean to be of a place? The play’s central characters are Aba; the Daughter; and the Land (all three played by Eliezer). In one of the play’s layers of time, we’re in present-day California, where the Daughter visits her father, her Aba,

who’s lost his memory.DAUGHTER:

No he’s good otherwise, still physically strong and charming as ever, although he’s been losing things lately: his hat, his dentures, his memory. Both his long short-term and his short long-term memories are shot.

He’s still himself, though, charming as ever, preening when the Daughter tells him his new haircut makes him look sexy.

Aba speaks in gibberish, which the Daughter describes as a choice.DAUGHTER:

He’s not really into words much anymore.

But the Daughter is missing her memory too. Aba has moved through the world since before the Daughter’s birth as an assimilated American Jew from Israel. “Something’s missing,” the Daughter repeats throughout the play. Something doesn’t add up. Why does Aba sing a melody that stands out, in their California synagogue, as different? Why didn’t he teach her?

What is this piece of map he’s swallowed?DAUGHTER:

Aba! Sometimes I feel like I’m standing on a carpet in the desert, holding a map to a place I’ve never been. You’re there. You reach out, tear the map into pieces and swallow it. The carpet takes off. I can’t see you anymore.

In another layer of time, we are with Edward: Aba as a boy, growing up in Baghdad in the 1930s and 1940s. He’s one of 80,000 Iraqi Jews in the city at the time (and 130,000 across the country).His story is patchy, like a blacked-out transcript,LAND:

You and I both know you paid a price to disregard, dis-member, dis-place yourself. full of jumps and caesuras.EDWARD:

Memory is a deceptive carpet ride into the soul. Thanks to the protection of a Muslim neighbor and friend, Edward and his family live through the farhud in 1941, a pogrom in Baghdad that kills close to 200 Jews. The family stays, as indeed most do; a mass permanent departure of Jews from Iraq won’t occur until the early 1950s.ABRAHAM:

As long as the talented and beautiful Salima Pasha Murad remains in Baghdad, I will be here, standing on this carpet, listening to her.

Beloved Iraqi Jewish singer Salima Murad (1905–1974), nicknamed "Pasha" by the Iraqi Prime Minister Nuri al-Said, who stayed in Iraq until the end of her life.

In the meantime, Baghdadi Jews rebuild fast: new schools, new homes, new hospitals. They’re politically engaged—some become Zionists, “but many more [wave] the red flag.” Many who left immediately return following the farhud.

Still a child, Edward joins the Zionist underground.ABA:

So I joined the underground movement, the young Chalutz the same year as the Farhoud: 1941...I was so happy, we used to meet every week 30, 40 boys and girls. I was 11, 12, 13 years old, smuggling weapons to the big basement of my home. And I worked very hard, digging with my fingers, to make another 4 foot, another 4 foot. My father doesn’t know what I am doing, he would never approve. Years later, as a teenager, he leaves Iraq to join the kibbutz movement. It’s a passionate choice for him, but a desire to go to Palestine is far from the prevailing sentiment among Iraqi Jews.OVADIA:

So much complaining to go to the desert and live in tents. Why go to Palestine at all, Hajjar? There are more Jewish Communists in Baghdad than these upstart Zionists. My brothers, we Communists will never leave this country we helped build! Once Edward leaves Baghdad, he is gone for good. And this is where his origin story, for the purposes of the play, breaks off. It ends where Aba believes he begins, at his transformation from Edward to Uri. The Edward we see is a person he tried to bury in time.DAUGHTER:

Aba is Jewish and Israeli.

You have to say, “Aba is Jewish and Israeli”

Yeah, okay he was born in Iraq

but he’s Israeli,

because

because

it’s as if if he was born in Israel

because Israel was born with him.

He always said “We were Israel before Israel was Israel.”

So

So

(begins to breathe heavily, perhaps choking back words, Arabic sounds)

(dis)Place[d] is part documentary and part auto-ethnography; the nameless Daughter is Eliezer. Most of Aba’s words in the show, and his stories, come from a film of her father that Eliezer put off watching for eight years. She knew that if she watched it, she says, she’d have questions, and if she had questions she’d need to make a show, and making a show would be hard. Once you open up a memory, you’re making yourself vulnerable to everything that might have happened to it in storage: bits gone missing, deterioration, rot.

Time lapse on top of time lapse. Chasing memory and fearing it, at once. The source of the story’s blackouts are multiple: Aba’s self-exile into intentional forgetting, Eliezer’s indirect and delayed access to his memories after his death, and

the distance between Iraqi Jews of Eliezer’s generation and Iraq as place, as land.LAND:

You think you can hide from me? I’m a part of you.

You breathe me, you dream me.

Your lips long to sing my song.

DAUGHTER:

I don’t know you!

Aba said nothing of YOU

Except that we would never see you.

Because WE are Jews

NOT Arabs

WE speak Hebrew

NOT Arabic

Iraqi Jews on the Tigris River, circa 1959, around the time Edward would have left Baghdad. Photo: Maurice Shohet via Iraqi Jewish Archive.

***

A refrain through the play: the Daughter has a dream. After she wakes, she forgets the details, but remembers the feeling.DAUGHTER:

Aba, sometimes I feel like I’m hammering a house I don’t recognize into my heart. You grab the hammer and it turns into a gun. You pull the trigger. And it bursts inside my chest...Later I forget the details. But I remember the feeling.

She forgets the details because she doesn’t have the words for them. She’s longing for a context that no longer exists. Not having the words is more than not speaking Arabic; the community in her dream is gone, its people scattered, its relations broken, its complex situations only memories. She could learn the language, but that isn’t it; that isn’t enough to understand. She could return to the place, but the place is a memory, the memory buried under violence, displacement, and fear; under conscious forgetting and assimilation.

How do you speak to the past? How do you hear the language of your bones? Can it be tasted or smelled?DAUGHTER:

Aba, I’m trying to make those meat dumplings—Kibbee? Kibbeh?—like Aunt Raquel made for me, when I went to Israel. But every time I go to the Middle Eastern store,

(whispering,)

it’s weird. I feel like I have the language in my mouth, but when I open it, English falls out.

What did you speak at home, Arabic or Hebrew?

Something is missing.

You can collect the pieces separately but they’re impossible to reassemble. From this vantage, land and landscape merge into one another to refer to a physical site where beings can be, where things can be located, where actions can happen. This is the kind of land that can be owned, in the sense that someone or some state can muster enough power to say: these beings may be here, and these others may not. These actions are tolerated here; these actions are unacceptable. In this concept of land, Jewish Baghdad and other scattered communities can get wiped off the map, with nothing left for their descendents but nostalgia and assimilation.

Eliezer as the Daughter. After Amherst, (dis)Place[d] toured Chicago and the United Kingdom. Photo: Wendy Yalom.

What if we understand landscape to mean a kind of spatial relation that’s much more mobile than land, and temporal? Could we understand our attachment to place differently if we paid attention to how landscape can

call and re-call us through our bodies, and through memory that need not be our own?DAUGHTER:

And in the way you chanted in synagogue: Those long, meandering sounds sent my heart traveling far away from the suburbs I knew. Each piece of knowing you complicates the me I believe myself to be.

A friend of mine grew up in rural Pennsylvania, a place small and green, where hills are the most striking geographic feature. In her twenties, this friend visited the little Hungarian town from which one branch of her family stemmed. She had never seen a photograph of it. Approaching the town in her rented car, she rounded a bend and experienced a sudden, vivid feeling of coming home. Hearing her recount it, what interested me was the feeling’s lack of mysticism. It was logical, direct: this looks like home. The land that opened out in front of her as she drove was hilled and green; the size and contours of the hills were just like the Pennsylvania hills among which she’d grown up. She remembered the story that her great-grandparents, Hungarian immigrants to the United States, had settled where they did because it reminded them of home. A sense of what makes home can generate a nostalgic attachment to place but it can also determine where a new home gets made; a landscape can stow away like this, across oceans, across generations.

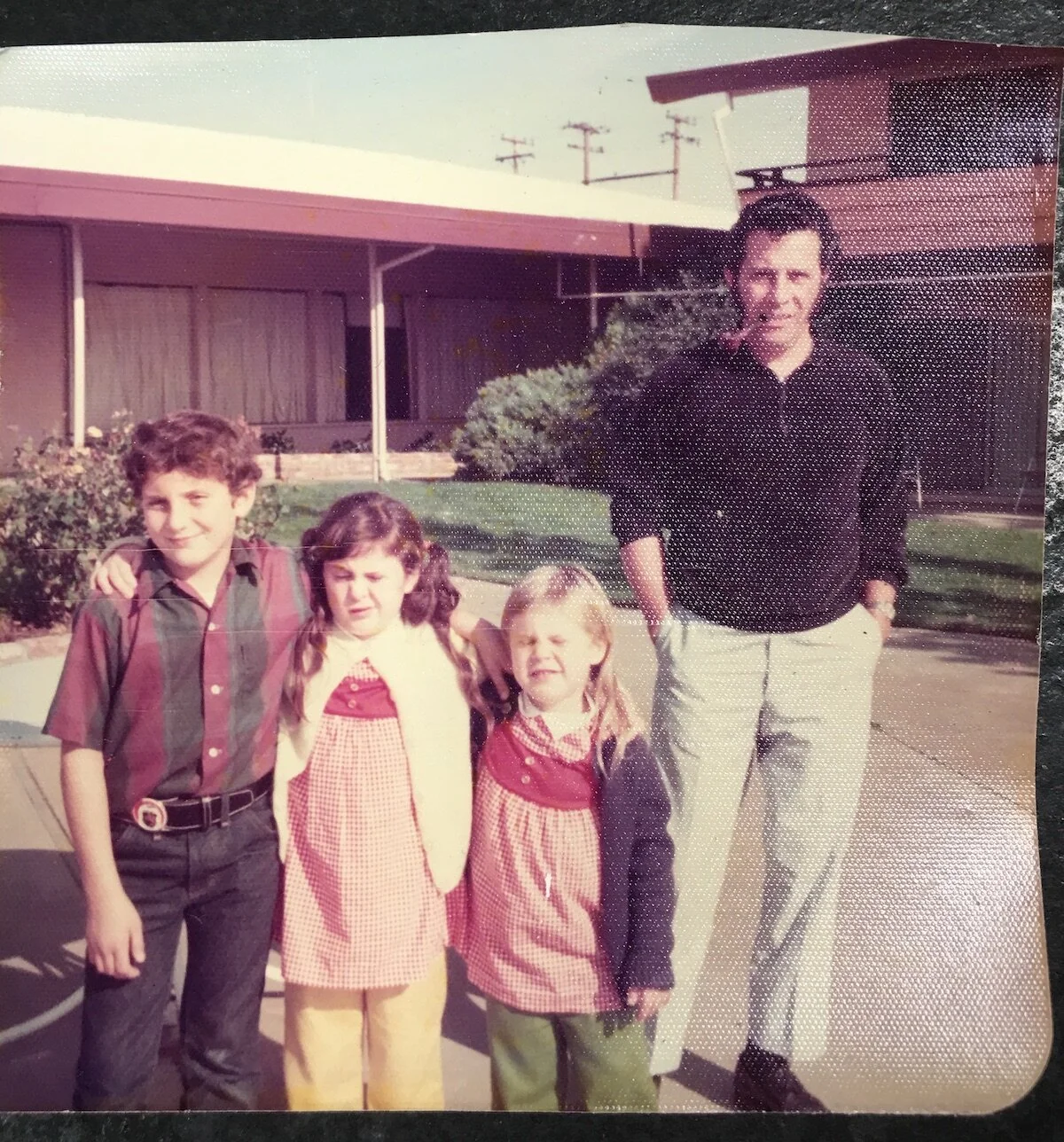

Eliezer, between siblings Daniel and Hagar, circa 1974. Behind them, Aba smokes a pipe. Photo: courtesy of the artist.

In (dis)Place[d], the character of the Land is a stowaway in the Daughter’s body. Eliezer’s performance under Ben Yalom’s direction makes this visible through wordless vocalization and a movement vocabulary that haunts or possesses the Daughter. The Land speaks to her; the Land speaks through her. At our farm-fresh breakfast, Eliezer tells me that the character’s roots were aural. Her father’s chanting in synagogue, just different enough to catch her ear as a child, filled her with questions. How can he be from a place “not too far from this other place, or this other place,” and yet sound so different? What is the sound of the desert? What is the sound of place? In the play, she grapples with these questions in half-dreaming sequences: her hands, torso, hips move in recurring patterns that make no sense to her or to the audience, like she’s navigating an invisible terrain by feel and instinct. She chokes on words that fill up her throat but that she can’t speak, an Arabic she never learned. Words take on substance, becoming flavors, pieces of earth, smells. Through her, the Land speaks—and puts Aba in his place: Aba, who thinks he can control his children’s memories, who believes he made the desert bloom.

The way the play was made is another way of highlighting that our bodies always carry more than our selves. Though it’s a solo performance, it’s also a production of foolsFURY, a San Francisco-based physical theatre company that has created and performed shows as an ensemble since 1998. A solo show is an unusual undertaking, both for Eliezer and for the company. But the rest of the ensemble, though physically absent, is still a part of Eliezer’s piece. She used the ensemble’s methods of devising to create and write the play. The company’s physical approach to storytelling shaped the way Eliezer and Yalom staged it. Their longstanding creative relationship, a hallmark of an ensemble theatre model, also meant that he was deeply familiar with her range and her strengths as a performer. Knowing her particular skill as a character actor, he encouraged her to write a multitude of voices into her script and worked with her to make each character physically and vocally distinct. “We are an ensemble,” Eliezer says. “When you see me onstage, you’re seeing my training, and you’re seeing all of my other company members.” Seeing the labor of many in one, understanding solo performer as multitude, holds particular weight in the context of a play about who and what we carry in us, in our gesture, in our speech.

And, finally, the play is auto-ethnography, which has a particular kind of effect in performance because you feel like you’re watching the methodology happen. The work of the play is more than Eliezer’s storytelling or her confident shifts from one character to another.

The work of the play is that night by night, in every performance, Eliezer travels into herself, trying to map this internal and foreign landscape, trying to find the spell that will transform her breath into words and her blood into memories.DAUGHTER:

Aba! Sometimes I feel like I’m coughing up the letters of a language I don’t understand. You’re there, cupping your hands under my mouth, catching every sound. I look into a mirror…My face becomes yours.

Later I forget the details. But I remember the feeling.

It feels unfinished, as such work must always be. It’s not important that this story is “true,” as much as it is that the questioning, seeking, and almost alchemical attempt to remember through the body are all real.

***

I am about to say something both true and impossible: (dis)Place[d] is a play about Arab Jews and it is not a play about Israel-Palestine.

It’s true in the sense that it’s a story about an American-Iraqi Jew trying to understand her relationship with a land and language that her father erased from his own conscious memory but that lived on in his body and now in hers. It’s impossible because to say the words Arab and Jew together is to evoke Palestine and to problematize Zionism’s ideological partition between Arab and Jew. The (dis)Place[d] artistic team knows this, and tries to tackle it directly in the play through a recurring scene—a dinner partyB:

Is this chardonnay organic? I’m—

DAUGHTER:

Uhhhh—

B:

—worried about sulphites.

A:

(to C)

Come on, just admit it: Israel is a white country surrounded by brown countries.

C:

That’s so racist.

B:

You should put that in your show! with some truly obnoxious guestsDAUGHTER:

Actually, there’s a lot of “brown” Jews, too.

B:

Are you gonna put that in your show?

C:

Race is passé, a 19th century social construct.

B:

Are Jews a religion or a race? I never got that... who claim to know better than the playwrightA:

Social, biological, mythical, whatever. It’s about race. That’s what your play is about.

C:

No, it’s about the right to exist. That’s what it’s about!

A:

No, it’s about the brown Palestinians being oppressed by the white Israelis. what her play is about.C:

What?! After 6 million Jews were killed, the survivors shouldn’t have a homeland?

A:

And that justifies the incredible—

DAUGHTER:

Stop! Stop! That’s not the story I’m telling!

B:

Then, what is?

DAUGHTER:

It’s about...what’s missing, what’s...absent. This is the play’s least successful sequence. No father can control his daughter’s memories and no artist can control the associative qualities of her work. Approaching the matter head-on can even make things worse: to be able to say “This is not a story about X,” you’ve got to bring up X, and then there X is, in the room, called up.

Palestine, called up in this context, forces some real questions about any kind of cultural production looking to counter the erasure of thousands of years of Arab-Jewish history. How does one approach such a project without furthering what Eliezer calls “Ashkenormalization,” without contributing to a settler-colonial project of firsting and lasting? How can all Jews learn and honor a fuller Mizrahi Jewish history without contributing to a Zionist narrative that seeks to instrumentalize this history in the name of Jewish land sovereignty claims in Israel-Palestine?

Eliezer in (dis)Place[d]. Projected behind her is an archival photograph of her father as a young man. Photo: Ben Yalom.

The best answer (dis)Place[d] has to these questions is not in the dinner party scenes. It’s in the way that the performance gets curious and stays curious about how people carry landscape with them—landscape as land and cultural practice. The play stages what it means to carry land inside of you and to grapple with how it shapes your thoughts, words, and relationships. It deals with what happens when the landscape inside of us is suppressed. It’s a stranger telling the story of a place to herself: as of this writing, Eliezer, though she has been to other parts of the Middle East, has not yet been to Baghdad. The land is in her body, but her body has not been to the land. The character called Land doesn’t represent an Iraq past or present as much as it does an interior, very personal landscape.LAND:

All those thoughts before you wake up?

That’s me.

That anxiousness, that fear.

That’s me.

Don’t discount yourself, little one. What’s missing is right here.

That language, that song stuck in your throat is a living tattoo.

An unregistered latitude and longitude on the map that needs to be put right.

You can avoid the map,—

but eventually the map finds you. When the Land speaks of “hot sand, cool desert wind, sweet river water,” it’s Eliezer. “This is a very Western piece,” an audience member once told Eliezer. Yes, and rightly so: (dis)Place[d] shows us a reconstruction of that mingling of distance from and desire for a homeland that could only have been created by someone who has not yet visited it. Aba represents a traditional geography of nations and borders that associates land with identity and forces him to choose between nostalgia and assimilation. Severing his physical relationship with the Land means he must cut all ties with her. Searching for the traces of Baghdad in herself, trying to fill the gaps in memory left by intentional erasure and rot, the Daughter/Eliezer connects to land(scape) differently. Here landscape is an active internal force that shapes her relations and animates her as she moves through the world. Many more such stories are needed to map the varied terrain of Arab-Jewish memory, and to free each individual story of the imperative to bolster a single political perspective or narrative of events. The play puts Zionism to the side. Writing about it, I’ve struggled with whether I can too. The answer now, when most of its audience won’t be able to, is: not entirely. But I can say that the play helps me think toward a poetics of landscape that can act with and because of a place, rather than enact upon it. If such a relationship with place, nurtured through story, becomes widespread among people whose histories settler narratives seek to exploit for their own ends, it could be a powerful antidote to such exploitation. And this, for me, is the liberatory potential in Eliezer saying I am of you, and inviting her cousin to join her in saying so, and other Iraqi Jews, and other Arab Jews.

I’ve finished my omelet. Our server comes to clear our plates. Hearing a snatch of our conversation, he asks Eliezer if she speaks Hebrew. She does. She’s Iraqi, she says. His voice lights: “Me too.” They begin to talk rapid-fire, animated by the discovery, fate’s small, neat acts. His family is from Baghdad and Basrah, he says. His great-great-great grandfather was the Chief Rabbi of Baghdad. “You’re blowing my mind, dude!” Eliezer exclaims. She turns to me, gestures. “Look at the face of an Iraqi Jew.” Another missing bit of the map has found her.

~

Notes

From Debórah Eliezer: An Abbreviated Bibliography

Books:

The Flying Camel: Essays on Identity by Women of North African and Middle Eastern Jewish Heritage, Loolwa Khazzoom (editor)

The Dove Flyer, Eli Amir

Poetic Trespass: Writing Between Hebrew and Arabic in Israel/Palestine, Lital Levy

Sweet Dates in Basra, Jessica Jiji

My Body, the Buddhist, Deborah Hay

“Cultural Identity and Diaspora,” Stuart Hall

Poets:

ABOUT THE ARTISTS

Cory Tamler (writer) is a multidisciplinary artist, writer, translator, and member of the GrayLit Editorial Collective. She is a doctoral student at The Graduate Center, CUNY.

Debórah Eliezer (she/her; performer/playwright, (dis)Place[d]) is a white/MENA theater maker and social activist. She is the newly-named sole Artistic Director of foolsFURY Theater, and an Associate Member of Golden Thread. Passionate about the power of human transformation, her work focuses on disrupting assumptions about art, human values and society. She has created and performed in numerous world premieres, working with playwrights Kate Tarker, Fabrice Melquiot, Angela Santillo, Sheila Callaghan, Doug Dorst, Yussef el Guindi, Denmo Ibrahim and Torange Yeghiazarian and Ben Yalom. With foolsFURY, Eliezer wrote and tours (dis)Place[d] which will be featured in Michael Malek Najjar’s forthcoming book, Middle Eastern American Theatre: Communities, Cultures and Artists. She holds a BA Cum Laude from SFSU and a certificate from CIIS. Eliezer is an artEquity arts facilitator alumna, and serves on the MENA Alliance of Theatre Makers committee (MENATMA) and Alliance of Jewish Theatres antiracist committee.

![Debórah Eliezer as the Daughter in (dis)Place[d]. Photo: Wendy Yalom.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55bae83fe4b0d7157ace5b3a/1590246470242-Z2NJOEVB356DKJ0BBUBL/Debo%CC%81rah-Eliezer-in-disPlaced_-part-of-foolsFURY-Theater_s-Role-Call.-Photo-by-Wendy-Yalom-2.jpg)

![Eliezer as the Daughter. After Amherst, (dis)Place[d] toured Chicago and the United Kingdom. Photo: Wendy Yalom.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55bae83fe4b0d7157ace5b3a/1590182527318-H29KIXTNHKOC2OB9KS0Z/Debo%CC%81rah-Eliezer-in-disPlaced_foolsFURY-Theater-Photo-by-Wendy-Yalom-web.jpg)

![Eliezer in (dis)Place[d]. Projected behind her is an archival photograph of her father as a young man. Photo: Ben Yalom.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55bae83fe4b0d7157ace5b3a/1595121262916-QH0WTM54HTUPUXKT2AI3/deborah_eliezer_in_displaced._photo_by_ben_yalom.jpg)